Nothing breaks the ice with preschoolers quite like reading Dr. Seuss. Friendships emerged quickly from the chaos of breakfast and playtime as Julia Wonsettler read “Oh, The Places You’ll Go” to a group of students in a classroom at Catholic Community Services’ Pio Decimo Center in Tucson, Ariz.

Wonsettler, a freshman in the physician assistant program at Gannon University, had journeyed a long way to share this moment in late February. She and seven other students from Gannon’s Erie campus spent eight days in southern Arizona as part of an Alternative Break Service Trip, or ABST, to explore immigration at the U.S./Mexico border.

This trip was one of six ABSTs that sent 45 students out into the world during spring break. Two groups traveled to Arizona while others served in Kentucky, Guatemala, Mexico and Ecuador. These were the first international trips since the pandemic began in early 2020.

ABSTs are weeklong service experiences designed to broaden students’ worldviews and to foster global citizenship through work and relationship-building in unfamiliar settings.

For Wonsettler and her ABST companions, that work started in a classroom for an organization that was founded to minister to the poor and hungry in Tucson’s Barrio Santa Rosa community, which has a significant population of recently settled immigrants to the U.S. The shared reading of Dr. Seuss preceded a week of hands-on service work.

The walls of the John Valenzuela Youth Center in South Tucson hadn’t been painted in 27 years. And you could tell.

A few days of work, however, transformed it.

“I can’t believe what a difference this makes,” said Jessica Alderete, the activities director at the center.

The more significant contribution came during the students’ breaks and at the end of the school day, when students would work or play with the children. One sunny afternoon, the Gannon students taught the children some of the fundamentals of volleyball and soccer. The children were still practicing what they had learned the next day and week.

“You can’t imagine the effect attention like this has on our children,” Alderete said. “Thank you so very much.”

Earlier in the week, she had explained some of the ways COVID-19 had disrupted families, education and the economy of southern Arizona. Two years into the pandemic, she said enrollment in her center is still down overall, and many children continue to struggle with attendance due to isolation or exposure.

Anthony Nunez, a freshman at Gannon University, paints a fence at the John Valenzuela Youth Center in South Tucson, Ariz.

Still, she said that’s not the worst of it.

“When the economy shut down, many lost jobs and had no way to support themselves. That brought on so much stress that many families just fell apart. Now, many of these kids are in foster care. Fortunately, many are fostered by someone in their family, but that’s not the same,” she said.

The U.S./Mexico border is also not the same. The recently built border wall has redefined the region, and it remains a point of contention in Arizona.

“It’s not what you think, or what you see on the news,” Raul Rodriguez said at lunch one afternoon.

Rodriguez was newly retired from the U.S. Border Patrol and had agreed to discuss his experiences with the ABST group. He had spent 23 years working along the U.S./Mexico border – much of it between Yuma and Nogales in Arizona. From his perspective, “the people coming over aren’t families, but usually 16- to 40-year-old men from all over the world. Many are criminals or sexual predators escaping their own countries. There are not a lot of families, like you’d think.”

There are also not a lot of drugs being trafficked across the border these days, he said. “Legalized marijuana in several states has hurt that trade.”

Instead, human trafficking is the real business along the border.

As for the border wall, he said he is a fan. It slows border crossers down enough for them to be apprehended, and it concentrates them to the areas where the wall ends and the old “Normandy fencing” resumes.

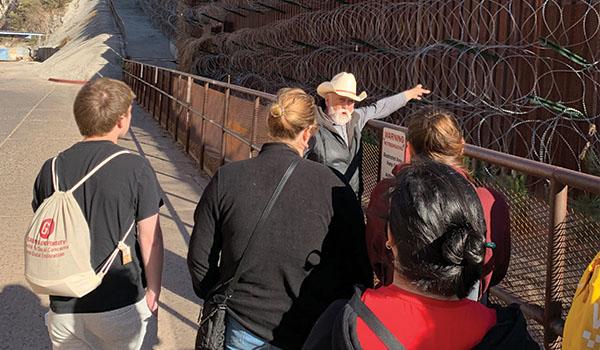

The Rev. Peter Neeley works on both sides of the border wall near Nogales, Ariz. He met with students during their Alternative Break Service Trip to offer some context about what the border and the new wall have meant to Nogales and to immigration in the region.

The Rev. Peter Neeley, associate director of education for the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Ariz., detests the border wall. His organization is a migrant ministry that works on both sides of the U.S./Mexico border, assisting people moving in both directions across the border and generally promoting safety and dignity.

He considers the wall an abomination and an insult to everyone working at the border. He works in Nogales, a major border crossing. The wall was built through the center of town. Late in the trip he walked the Gannon students down to the wall, discussing the challenges of human trafficking and the history of immigration as he stepped along.

This is such a waste, he said, standing at the wall. “Imagine using just some of the money spent on this wall to actually help people,” he said.

Before this, there was a simpler and lower fence, and a bustling economy on both sides of the border. The traffic was light on this day as it has been for some time – in part because of immigration policy but also because of COVID-era rules that limit commerce and visits to curtail spread of the disease.

Zumiyah, a student at the Pio Decimo Center in Tucson, Ariz., made friends with Gannon student Sarah DuBrul.

He told the students the wall is a daily reminder that we need to live up to Matthew 25:35: “For I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat. I was thirsty, and you gave me something to drink. I was a stranger, and you invited me in.”

Each night brought powerful conversations as students reflected on their experiences.

“I think it’s so easy to have an opinion about immigration from Erie, but I never truly even began to grasp it until I was standing under the border wall in Nogales, Ariz.,” said Chloe Adiutori, one of the student leaders of the trip and a junior pre-pharmacy major. “Talking with Raul, seeing the work that places like Pío Décimo and JVYC are doing, and even talking to Father Neeley have made a previously overwhelming and unapproachable topic for me easier to begin to grasp.

“Meeting and seeing people who physically work at the border, have crossed the border, have lived this experience make the idea of immigration a tangible thing. It’s not an abstract concept anymore, but rather, I see specific people in my mind,” she said.

It is evident that immigration defines many things in southern Arizona – not just the political landscape, but the local economy, the schools, and the demands on social services.

The ABST group stopped to pose at the border. Pictured from left to right: An Le, Brennen Grabowski, Sarah DuBrul, Anthony Nunez, Harley Johnson, Elizabeth Gural, Chloe Adiutori and Julia Wonsettler.

These are the kinds of experiences that tend to build in one’s mind once you’ve lived them. In the weeks after the trip, the Gannon students were still processing what they’d learned.

“I think that the quote of the whole trip that really stood out to me was from Father Neeley when he said you are never going to be able to grasp immigration, and specifically illegal immigration, if you have never felt desperation before,” Adiutori said. “He’s right. I don’t know that I will ever truly understand that feeling, but I think that being down there, experiencing the border and surrounding myself with the lived experiences of those communities has allowed me the opportunity to meet them halfway in a way that I never would have been able to before.”

By Doug Oathout, chief of staff and director of Marketing and Communications